Published to Energy Action Network website in August 2021

Presented during Energy Action Network’s ‘Lunch and Learn’ on August 12, 2021

Abstract

The trades workforce shortage is not a new phenomenon in the United States. According to a 2008 report by the Center on Wisconsin Strategy and the Workforce Alliance, a power sector survey showed that more than 50% of respondents predicted they would lose 20% of the trades workforce in the next 5-7 years.[1] That trend continues as more tradespeople retire, often without anyone to take their place. Vermont’s labor force alone was reduced by 11,500 workers between the years of 2007 and 2020 and the state ranks 4th in the nation with the highest portion of the population at retirement age.[2] In addition, during the years from 2012 to 2016, 4,000 more households moved out of Vermont than moved into the state.[3]

This comes at a time when Vermont is preparing to substantially ramp up energy efficiency activity as one strategy for reaching state climate goals established in the Global Warming Solutions Act passed by the Legislature in 2020. The law requires Vermont to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions to 80% below 1990 levels by the year 2050, with interim goals of 26% and 40% established for the years 2025 and 2030 respectively. The energy used to heat and cool buildings and to provide hot water (referred to as “Thermal Energy” or simply “Thermal” by many) accounts for 34% of GHG emissions in Vermont and is the state’s second largest source of GHG emissions. Improving energy efficiency and the use of clean energy technologies in buildings is a key strategy (or “pathway”) for meeting state climate goals. Vermont has invested already in expanding the delivery of energy efficiency, weatherization, and clean energy technologies and services to help households reduce energy costs and improve comfort, health, and safety. However, “while energy efficiency policies can create jobs, the available local workforce determines the scale and quality of implementation.”[4]

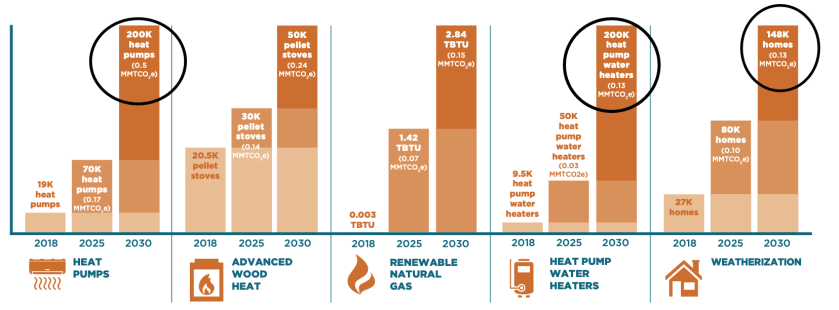

Over the past five years, the Energy Action Network (EAN) has invested significant time and effort into creating an Emissions Reduction Pathways Model which identifies and quantifies technologies and practices that can provide pathways for reaching Vermont’s climate goals. Among those in the pathway for reducing GHG emissions from thermal energy by 2030 are:

- 200,000 cold-climate heat pumps;

- 200,000 heat pump water heaters; and

- 148,102 homes weatherized.

Achieving this level of activity will require substantial ramp up and scaling of current market activity. Finding the workers to install and service the current level of market activity is already a challenge, and companies providing energy efficiency services who were interviewed all had waitlists ranging from one to six months. As noted in the 2020 Vermont Clean Energy Industry Report,[5] many companies currently providing energy efficiency and weatherization services in Vermont experience barriers to hiring including:

- A lack of workers with the required training, skills, and experience;

- A small applicant pool; and

- Insufficient qualifications among those who apply.

This is not unique to Vermont. According to a national study completed by the American Council for an Energy Efficient Economy (ACEEE), “80% of energy efficiency employers report difficulty in finding qualified job applicants to fill open positions.”[6] According to the 2021 Clean Energy Industry Report, Vermont currently has 9,832 energy efficiency workers, a decrease from 10,741 workers in 2020. The need for the rapid scaling of energy efficiency services in order to meet state climate goals for the building sector warrants new research on:

- How many workers will be needed to reach 2030 goals;

- Where the workforce will come from for filling those jobs;

- What education and/or training will be needed to prepare the workforce for those jobs; and

- What recruitment or other techniques will be needed to ensure the jobs are filled by workers

This report is the result of an EAN Summer Internship research project designed to address these questions. The project included estimating the future workforce needed to achieve state targets for reducing GHG emissions from energy use in buildings. Interviews were conducted with a variety of energy efficiency, weatherization, and clean energy companies to learn of their workforce experiences in the current market. Interviews were also conducted with state education and training leaders. An assessment was done of current and potential strategies for recruiting trainees and workers and retaining workers once they enter the energy efficiency, weatherization, or clean energy industries. Recommendations were developed for new strategies and initiatives for meeting future workforce needs. This report is the written deliverable from the research project. Results from the project were also presented virtually in a Lunch and Learn event delivered to members of the Energy Action Network.

Throughout the interviews conducted for this report, many lessons have surfaced regarding workforce development in the thermal sector. When designing and reforming current training and certification structures and practices, it should be kept in mind to break down formal certifications, build up supervisor capacity, increase on-the-job training, manage expectations, and improve the testing structure. Training curriculum should include broad, transferable skill sets, soft skills, and business skills to prepare students more holistically for success in the field. Training recruitment should focus on shifting the mindset and improving both affordability and conceptions of affordability, while employment recruitment should incorporate smart framing, mission-based recruiting, goals for positive work culture and retention, and strong partnerships. Opportunistic recruiting pools include high school students, the underemployed and unemployed, non-traditional labor pools, and workers from out-of-state.

In addition, this report provides many areas for future research and engagement. These include:

- Developing partnership outreach programs for companies that may not have established training-to-job pipelines;

- Incorporating justice-based training programs targeted for non-traditional labor pools;

- Developing mission and service-based volunteer programs or Corps programs;

- Incorporating do-it-yourself models into energy efficiency;

- Cautiously preparing for the possible of a ‘traveling tradespeople’ program; and

- Thinking creatively about ways to combine workforce, energy efficiency, and affordable housing.

Organizations and sectors like the Northeast Transportation Workforce Center, Cover Home Repair, Shires Housing, and Vermont’s Health Care sector have incorporated programs and models that introduce or incorporate these themes and can be used as inspiration for further initiatives.The workforce challenge is not isolated to energy efficiency, nor to Vermont. It is a daunting and challenging issue, but one in which many organizations and companies are already thinking creatively, and one that provides many opportunities both regarding the futures of Vermonters and the future of the climate.

[1] White, Sarah, and Jason Walsh. “Greener Pathways: Workforce Development in the Clean Energy Economy.” Community Wealth, 2008.

[2] “State of Working Vermont 2020.” Public Assets Institute, 2020.

[3] “State of Working Vermont 2019.” Public Assets Institute, 2019.

[4] Shoemaker, Mary, and David Ribeiro. “Through the Local Government Lens: Developing the Energy Efficiency Workforce.” ACEEE, 2018.

[5] “2020 Clean Energy Industry Report.” BW Research Partnership, 2020.

[6] Ibid.